The Distinctiveness Rationale derives from the concern that if corporate personhood remains, we will be forced to put corporations on the same constitutional footing as us. Because corporate personhood is nonsensical, it is illegitimate and therefore must be eliminated.

The underlying objection here is that law ought to be scrutable and understandable to those subject to it. Since even lawyers and judges acknowledge that it is a legal fiction, to base our political understandings of rights on such sophistry is to invite inanity into society. The Absurdity Rationale expresses the view that, because corporations are not conscious, living agents, corporate personhood must involve a category mistake. Corporate personhood ought to be abolished because the consequences are offensive to the egalitarian commitments inherent to a democratic society. The normative underpinning here is broadly speaking egalitarian in orientation. The Plutocracy Rationale stems from the fear that conceiving of corporations as bearers of constitutional rights reinforces the immense economic advantages they already derive from their legal personhood, thereby facilitating intolerable and ever-growing inequality in social and political power. We call the three basic arguments against corporate personhood the Plutocracy Rationale, the Absurdity Rationale, and the Distinctiveness Rationale. Three Arguments Against Corporate Personhood We offer a different way of thinking about the problem of corporate power, one that does not rely on abolishing the corporate person. We conclude that, despite their intuitive appeal, their various limitations show why the abolitionist cause is misguided. To explain why, our new paper identifies and reconstructs three partially overlapping but analytically distinct justifications for corporate abolitionism, which we express in general terms, independently of specific Supreme Court decisions or policy debates.īy showcasing the implicit philosophical logic underlying the three arguments against corporate personhood, we give them their strongest articulation and render them more scrutable to normative critique.

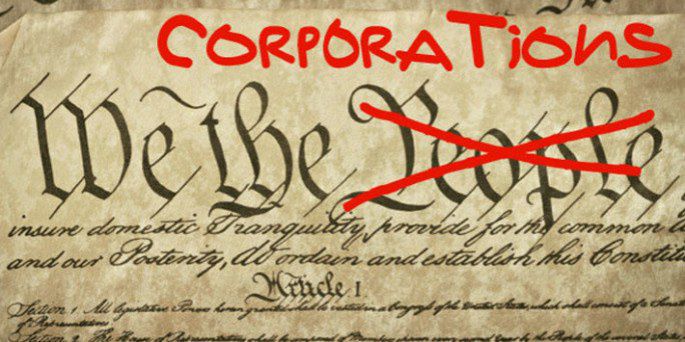

While we agree that excessive corporate power poses a danger to the functioning of modern democracies, like Kent Greenfield and others, we doubt that the proposed remedies are appropriate. Support for these proposals-that Susanna Ripken appositely labels ‘ corporate abolitionism,’ because, like the abolitionists of the 19th century, the movement frames its cause as an issue of human rights-has spread among local governments, state legislatures, and federal lawmakers. Rallying around such catchphrases is a broad social movement demanding that rights be restricted to human beings and corporate personhood be abolished. The powerful intuitions and normative concerns underpinning these objections are captured in familiar slogans, such as ‘End Corporate Rule,’ ‘Corporations Are Not People,’ and ‘We the People, Not We the Corporations.’ Critics argue that giving business corporations unwarranted constitutional protections entrenches corporate power at the expense of democracy by putting legal fictions on the same political plane as human beings. Considerable controversy has surrounded the US Supreme Court’s sharply divided decisions in Citizens United and Hobby Lobby.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)